The Result of Virginia’s “Awakening”

In part three, we saw that Connecticut’s harsh response to the religious Awakening drove New Lights south for continued revival in those colonies. Back in Granby, a decade of contention by two independent God-fearing sides ended in peace under the guidance of a new pastor, Joseph Strong. This 23-year-old carefully navigated differences without fire and brimstone obedience. Instead, he used gentler plain talk of “wisdom from above, which is peaceable, easy to be intreated.” He introduced New Light changes such as singing yet honoring the state church in principle. On the one hand, he baptized infants into membership while on the other hand he nurtured conversions by professions of faith in Christ.

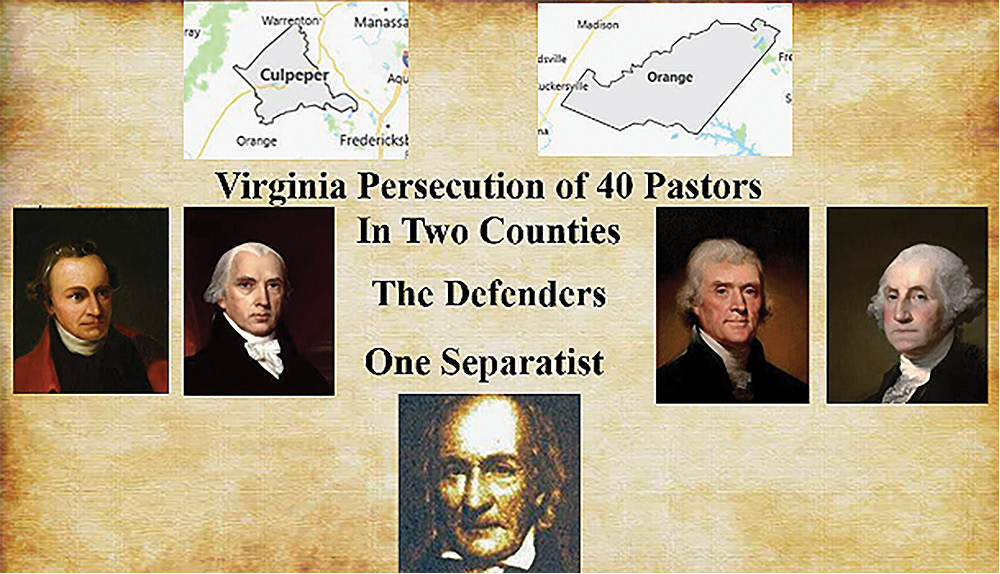

Meanwhile, the response by the Virginian Episcopal state church to the separatists was even more severe than in Connecticut. Jail time and more was served by over 40 pastors in Culpeper and Orange counties. Ironically, the greater the persecution, the bigger the crowds became to witness the punishment, including some of the Founding Fathers.

While praying after preaching, Pastor Jaime Ireland was seized by the collar by two men. He was given an ultimatum: promise not to preach there any longer or go to jail. He chose jail. He preached through the bars, despite all efforts to disturb him and the listeners. This included riding horses through the listeners, urinating in his face, attempting to blow him up with gunpowder, and suffocating him by burning brimstone under the floor of the cell. The jailer and a doctor tried to poison him, and he was dunked in water with the threat of further dunking and public whipping. He was placed in cells with drunks to harass him. Two women tried to poison his family, resulting in the death of one child and almost killing his wife. He personally suffered ill health because of this treatment, yet he signed his letters “from my palace in Culpepper.”

Pastor “Swearin’ Jack” Waller was jailed four times for a total of 113 days for preaching (“Swearin’ Jack” was his nickname before his conversion). On one occasion, it was because he conducted a worship service in his home. John Weatherford preached through the grates in the cell with hands out. Men slashed his hands with knives until the blood streamed down in front of those who listened to his message of redemption. After five months, the jailer refused to release him until the jail fees were paid, which happened anonymously. Some 20 years later, he found out the fees were paid by Patrick Henry.

Besides Henry, other Founding Fathers who lived in these counties came to the defense of the jailed pastors. Thomas Jefferson had attended Separatist Baptist church meetings, and the persecution influenced him to later write the Statute of Virginia for Religious Liberty. He requested that the accomplishment be recorded on his gravestone. George Washington was also influenced and would later write to the Virginia Baptist Association, “that if the Constitution might endanger the religious rights of any, I would never have placed my signature to it.”

James Madison was deeply disturbed by the degeneration of the clergy. At age 19 he penned, “the worst I have to tell you is that hell-conceived principle of persecution rages among some clergy. This vexes me the worst of anything so I must beg you to pity me and pray for the liberty of conscience to all.” In 1776, at age 24, he objected to the term “toleration” being used in the Virginia Declaration of Rights. “Out of duty to our creator” he insisted, “all men are entitled to the exercise of free religion according to the dictates of his conscience.”

Where did he get such thinking? John Leland, an evangelist from Massachusetts, was only 22 when he arrived in Virginia the year before. He was a leader of the separatist Baptists and a neighbor and close friend of Madison and Jefferson. In letters to Madison, Leland wrote that “government should protect every man in thinking and speaking freely” and that “the liberty I contend for is more than toleration.” Leland’s view of freedom was “that the notion of a Christian commonwealth should be exploded forever. Whereas all should be equally free, Jews, Turks (Muslims), Pagans and Christians.” In his writings and preaching, one was accountable to his or her creator for this inalienable (God given) right of conscience.

Next: How did this freedom of conscience and Madison’s Virginia Declaration of Rights in 1776 get to be the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1789?